Personalized learning is all the rage these days. Scan the latest headlines of major publications covering education, and you’ll inevitably come across lots of talk about classrooms where instruction is “individualized,” “student-centered,” and “customized.” So-called reformers from the ed-tech community especially favor this language, touting the latest software they’ve created to expertly deliver a curriculum to a passive learner in front of a computer or tablet.

In theory, no one should be against personalization. But if you believe, as many educators have for quite some time now, that learning almost always occurs in a social context, then some of this talk of creating an individualized curriculum for each child might give you pause. If one of our central aims in schools is to build vibrant communities devoted to learning, then we need to think about how individuals usually learn within communities.

In his landmark book, The Book of Learning and Forgetting, Frank Smith maintains that for millennia humans have learned from “the company we keep.” We are driven instinctively to seek out what he terms clubs – communities of influential people – and as we identify with the members of the club, we begin to establish our own sense of identity:

people – and as we identify with the members of the club, we begin to establish our own sense of identity:

…as we identify with other members of all the clubs to which we belong, so we learn to be like those other members. We become like the company we keep, exhibiting this identity in the way we talk, dress, and ornament ourselves, and in many other ways. The identification creates the possibility of learning. All learning pivots on who we think we are, and who we see ourselves as capable of becoming.

While there are undoubtedly times when individuals learn something on their own – for example, reading a book on a topic, perhaps to understand some new concept or to complete a task or a project – Smith insists that even in this case, one is joining the “literacy club,” joining the company of authors, participating in an exchange of ideas towards the ultimate fulfillment of one’s intended goal.

Learning within your club

So, along this line of thinking, we are constantly learning about our world, and there are a variety of clubs that we identify with that deeply influence this learning. Some clubs we are born into (i.e. the American club, the rural or urban neighborhood club,) and some that we are more naturally compelled to join (what Smith terms the “spoken language club” that all infants and toddlers join at some point.) The clubs that we choose to identify with not only influence learning, but actually create conditions for the kind of deep learning that we carry with us throughout our lives.

Looking at the clubs that our students at The Willows gravitate towards, I notice that there are, of course, certain common examples: some children identify with clubs centered around sports or games, others identify with art, music, or dance. By middle school, when the pressure to join one specific club or another seemingly intensifies, children begin signing up for clubs like Rock Band or the Robotics team.

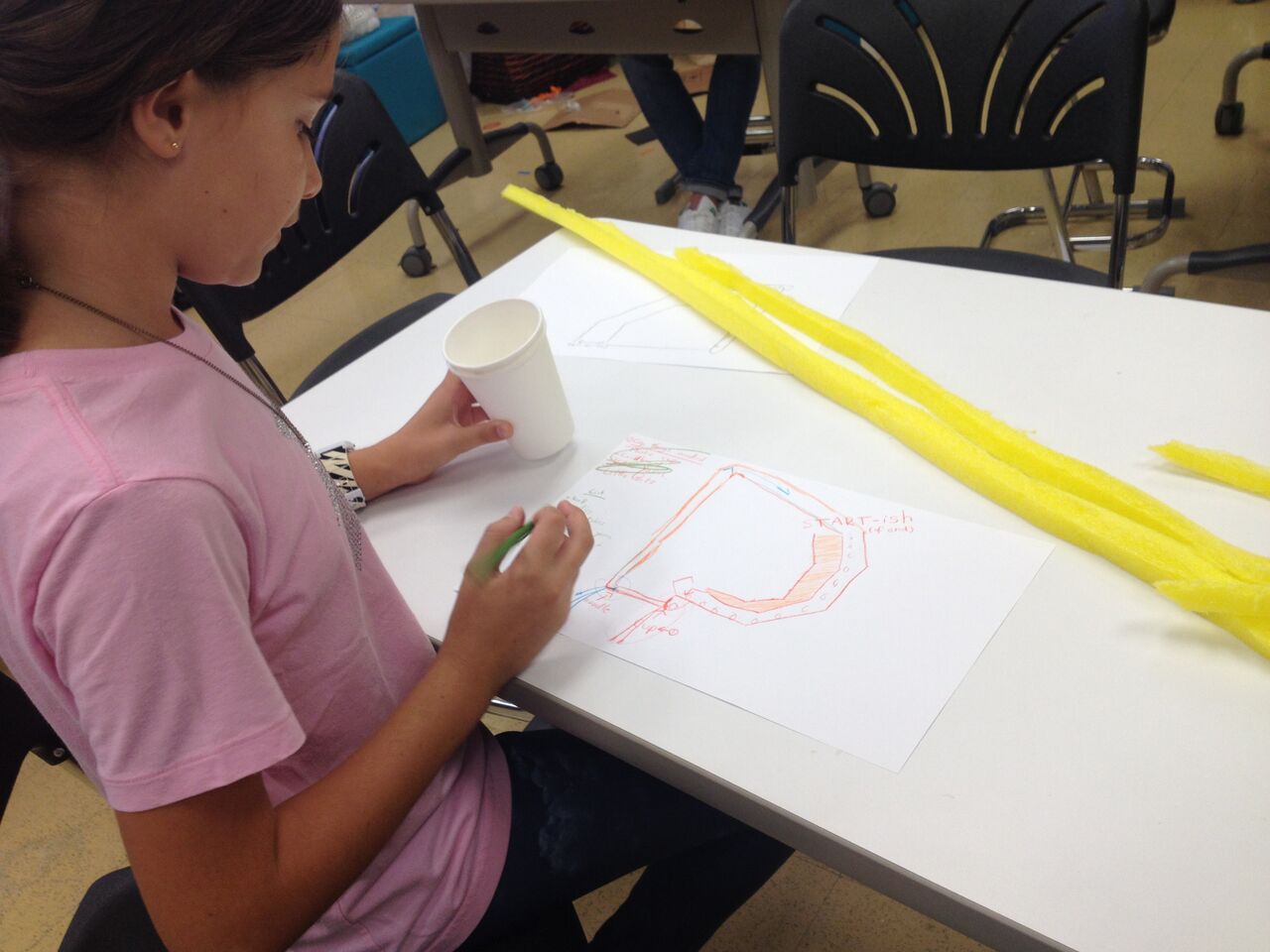

One new, informal club that has emerged this year is our Maker Club. Since establishing our makerspaces within the school two years ago (spearheaded by our Director of Technology Amy Dugré) and beginning weekly maker classes during the school day last year, we have wrestled with how to give interested students more devoted time to work on self-directed projects. This year, we found four blocks of  time, two lunch periods and two afterschool sessions, where students are invited to work alongside fellow makers and maker teachers, often learning new skills and developing deeper expertise with familiar tools and programs.

time, two lunch periods and two afterschool sessions, where students are invited to work alongside fellow makers and maker teachers, often learning new skills and developing deeper expertise with familiar tools and programs.

However, in addition to being interested in becoming a better programmer or learning how to print with (and often repair!) 3D printers, we have also noticed other worthwhile interactions amongst our Maker Club members. Kids are genuinely excited to have this time and space available, and are quite disappointed when we have to cancel Maker Club. One student’s excitement about their particular project has the real power to inspire others in the same room to try something new, leading to a scene we recently came upon, where four fifth grade boys were crowded around a Youtube video on how to use a sewing machine after seeing the pillow a sixth grade boy had recently finished assembling.

These observations align with some of the latest research on maker-centered learning, specifically research from a recent initiative associated with Harvard’s Project Zero. In a white paper reporting initial findings (that are being prepared for a forthcoming anthology called Makeology), the researchers found that “the most salient beliefs of maker-centered learning for young people have to do with developing a sense of self and a sense of community that empower them to engage with and shape the designed dimension of their world.” Young empowered makers, they argue, see themselves as people capable of finding and solving worthwhile problems, as individuals within a supportive community “who can muster the wherewithal to change things through making.”

Implications

Thinking broadly about identity and association, several questions persist:

- Are we aware of what draws us to our clubs, to the company we keep?

- Do we belong to different kinds of clubs, representing diverse or divergent points of view?

- Are we aware of clubs (or better yet cultures) that are different than our own?

- Is it possible to learn much about a club you are not a member of?

Further, given that all of us are compelled to join communities and learn alongside their members, what does this mean for us as educators? Exactly, how do these issues play out daily in classrooms?

For example, think of the students who have already decided by second or third grade that they are either deficient in reading or math (or both, or school in general); these students seek out classmates who feel the same and reinforce this desire to be a part of the “non-reader” or “math hater” club. What steps can teachers and school leaders take to deal with all-too-common phenomena like this?

people – and as we identify with the members of the club, we begin to establish our own sense of identity:

people – and as we identify with the members of the club, we begin to establish our own sense of identity: time, two lunch periods and two afterschool sessions, where students are invited to work alongside fellow makers and maker teachers, often learning new skills and developing deeper expertise with familiar tools and programs.

time, two lunch periods and two afterschool sessions, where students are invited to work alongside fellow makers and maker teachers, often learning new skills and developing deeper expertise with familiar tools and programs.