“50% of all mathematics was invented after WWII” – NCTM, 1989

This piece of information was displayed during an introductory presentation at the Reinventing Mathematics Education Symposium held at the Willows on our first day back from winter break. And so began a fascinating day of learning that served to not only challenge many of the beliefs and assumptions teachers have about math education but to also push us to envision what’s needed to truly make math engaging for all students going forward.

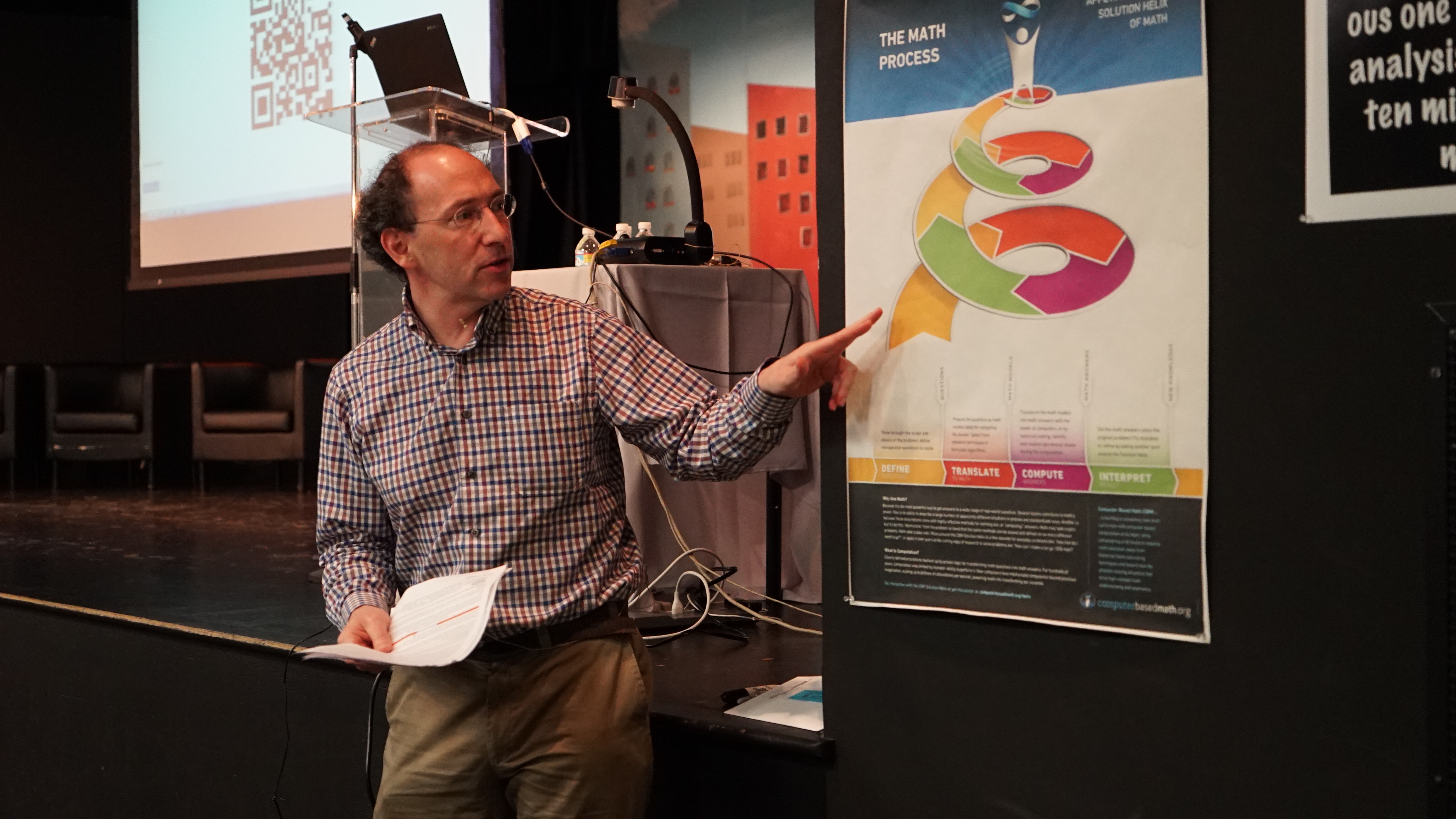

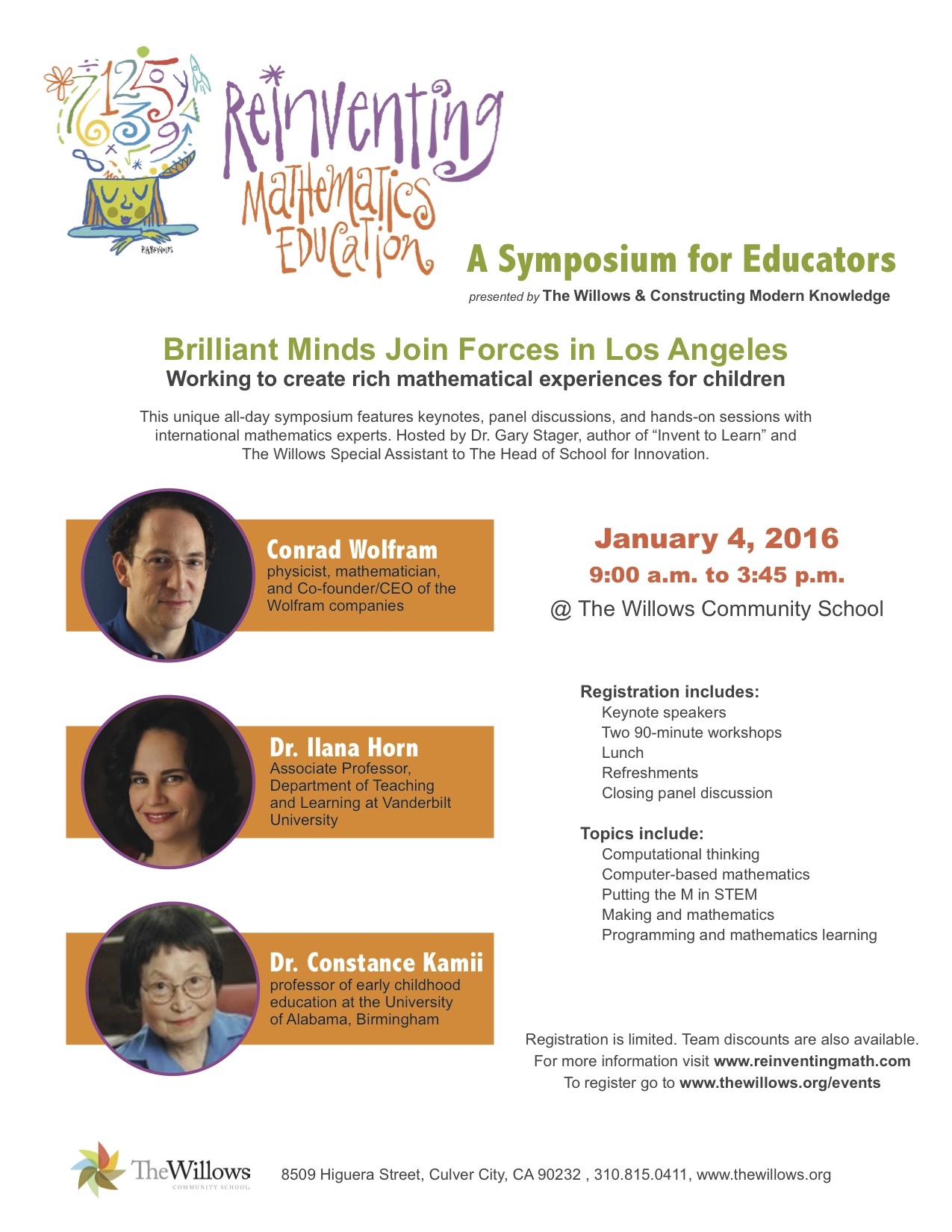

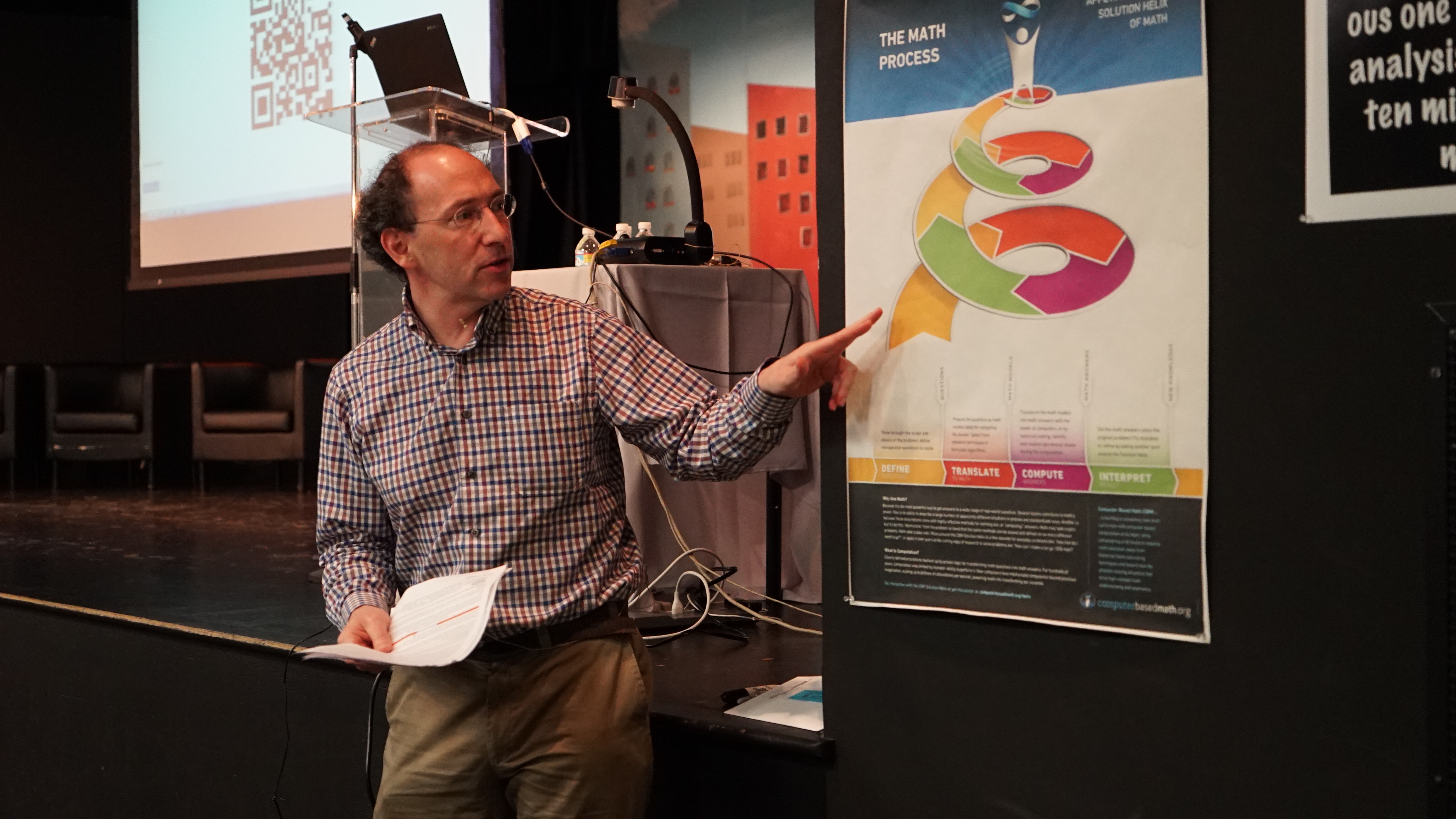

Organized by our esteemed Special Assistant to the Head of School for Innovation Dr. Gary Stager and our Director of Technology Amy Dugré, The Willows hosted roughly 80 educators from all over the U.S. plus international attendees from India, South Korea, and Australia. Keynotes, 90-minute workshops, and a concluding panel were offered by presenters Dr. Ilana Horn, Dr. Constance Kamii, and Conrad Wolfram.

Key ideas

Throughout our day, each speaker lamented the current diet of mathematics offered in schools, which leads to widespread student disengagement and a lack of appreciation for math as a connected, meaningful and beautiful subject. As mentioned in my last post , many teachers feel uncomfortable teaching math, and students see math as a separate, almost alien segment of their school day, where pointless problems and procedures are put before them, often resulting in confusion or, even worse, regular blows to their self-esteem.

So, what else is possible? Each speaker shared different thoughts on the subject, and each brought unique perspectives from their research and experiences to share with our attendees.

Overall, listening to each presentation, I felt like there were three main underlying questions that were addressed:

- What should math class look like?

- How do young children build math understanding?

- What should we teach in math class?

Let’s take a look at each in a little more depth.

What should math class look like?

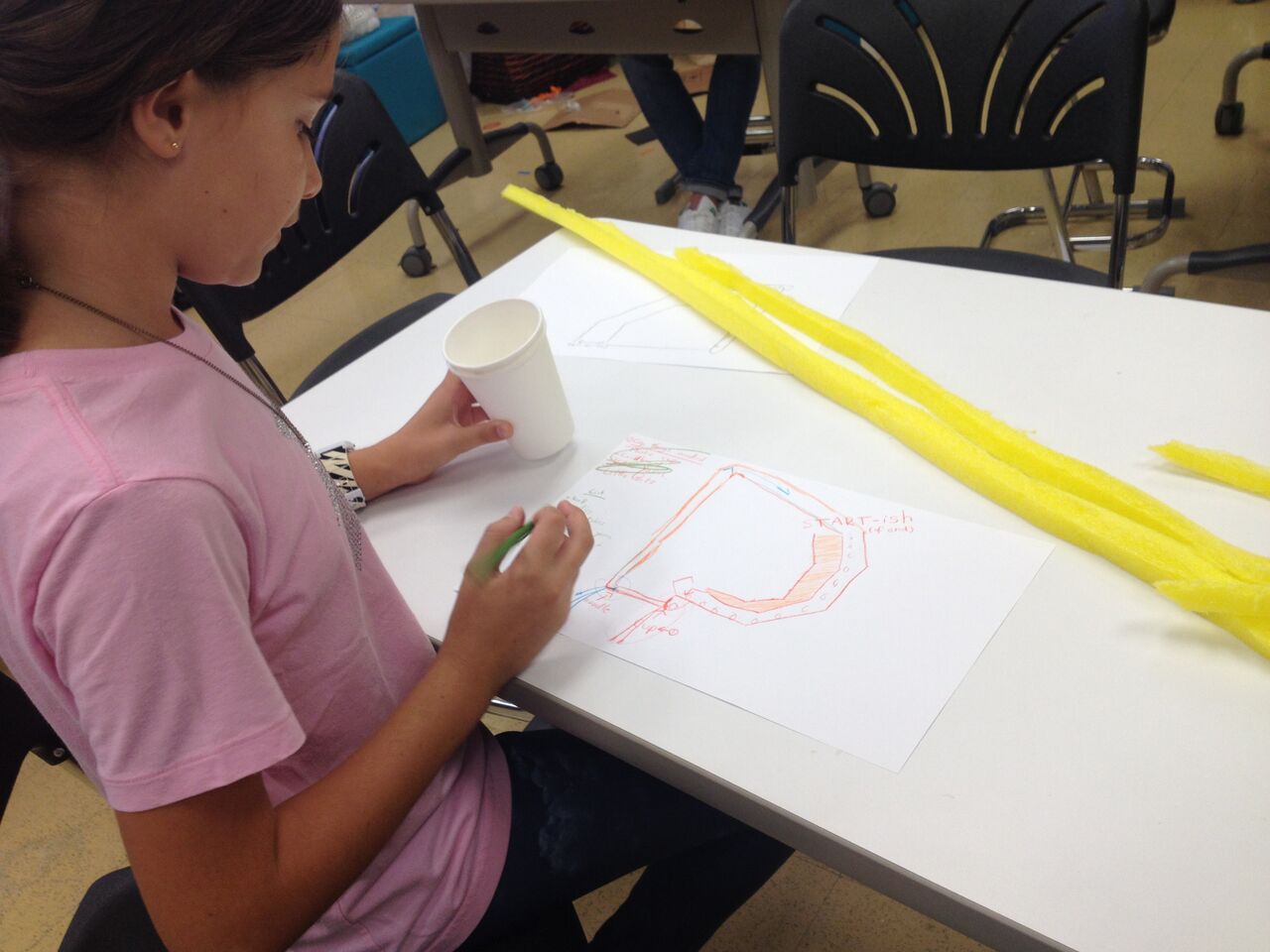

We heard first from Dr. Ilana Horn, Associate Professor at Vanderbilt University, whose research has focused on creating conditions in classrooms where all students feel comfortable exploring mathematical ideas within supportive environments. She spoke about math class being a “risky” environment for many kids, where the benefits of not participating greatly outweigh the rewards. To lessen risks towards lowering social and academic standing amongst peers, she suggests we should show kids that math class can be a bit of a playground, where instead of our current overemphasis on right or wrong answers, we present interesting, playful problems worth engaging with. One example of this she offered was a problem asking students to create a bungee jump for a Barbie doll; the challenge is to give Barbie a thrilling ride while still keeping her safe (i.e. don’t let her touch the floor).

Later, in her workshop, she presented some interesting insights into two important elements teachers need to consider when choosing activities for math class: status and smartness. Horn defined status as the perception of academic capability or popularity, and stressed that students will make decisions about participating in math class based on their (often faulty) perceptions about how their standing might be affected.  Regarding smartness, she asked us to consider who students usually consider to be smart in math: those students who are the fastest and most efficient with calculating. Much like Conrad Wolfram, Horn insisted this is much too narrow a view of what constitutes smartness in math. To illustrate her point, we watched part of a TED talk from Pixar animator Tony DeRose, where he highlights the math involved in creating animation, hardly any of it involving the kind of calculation-based activities that normally dominate math instruction.

Regarding smartness, she asked us to consider who students usually consider to be smart in math: those students who are the fastest and most efficient with calculating. Much like Conrad Wolfram, Horn insisted this is much too narrow a view of what constitutes smartness in math. To illustrate her point, we watched part of a TED talk from Pixar animator Tony DeRose, where he highlights the math involved in creating animation, hardly any of it involving the kind of calculation-based activities that normally dominate math instruction.

How do young children build conceptual understanding?

Piaget teaches us that it is not the job of the teacher to correct a child from the outside, but to create the conditions in which the child corrects herself from the inside. – Dr. Constance Kamii

According to Kamii, whose mentor was the father of constructivism, the Jean Piaget, the answer is simple: children build conceptual understanding on their own, independent of (and sometimes in spite of) the teacher’s instruction. “You can’t put numbers into children,” she insisted, claiming that a whole lot of useless instruction takes place in classrooms, trying in vain to get students to understand number concepts. What’s worse, she said, adults have invented standards that claim all students of certain ages should be able to do certain mathematical tasks, when decades of research contradicts this very notion. In her words, “You cannot teach the concept of multiplication to children who haven’t invented the concept of multiplication yet.”

During her workshop, Kamii led teachers through a variety of card games designed to build a stronger number sense in primary-aged students. True to her constructivist perspective, she was emphatic that these games be played independently of any formal math instruction – that is, teachers should not be pointing out to students that they are adding or subtracting before, during, or after playing the games. Students must construct their own meaning, and this is achieved only through repeatedly playing the games, revisiting the concepts over and over again.

True to her constructivist perspective, she was emphatic that these games be played independently of any formal math instruction – that is, teachers should not be pointing out to students that they are adding or subtracting before, during, or after playing the games. Students must construct their own meaning, and this is achieved only through repeatedly playing the games, revisiting the concepts over and over again.

What should we teach in math class?

I summarized much of Conrad Wolfram’s position on reinventing math classrooms in my previous post and his keynote at the Symposium touched on many of the same key points covered in his TED talk. Briefly, Wolfram’s key assertion is that far too much time is devoted in math classes to teaching calculation by hand; math is first and foremost a powerful tool for solving problems, and we should be teaching students to develop the ability to solve complex, worthwhile problems and outsource the calculating to the computers. He also underscored the importance of programming, which is essentially a notation system used to express mathematical ideas.

In his breakout session, Wolfram took us through a few computer-based math activities, demonstrating how the tools his company have developed could be used to help students work with large data sets to solve interesting problems like “Are Premier League Officials Biased?” He also took us through some activities from the Wolfram Programming Lab, a free service that allows users to develop programs using Wolfram Language, the same coding language used to power WolframAlpha, their powerful online tool used by research and development organizations all over the world.

One notable idea that Wolfram shared is that we should be noticing and investigating the presence of mathematics in all subjects. Understanding patterns and the underlying logic within systems amongst a wide range of disciplines is a valuable skill worth cultivating in all students; math, he argued, is needed in today’s world for “logical mind training,” essentially a system for being able to think about how best to solve problems.

One lingering question that I had even after hearing from Wolfram was if 50% of mathematics was invented after World War II (he actually estimated that it was probably closer to 90%), and we shouldn’t be spending so much time on teaching hand calculation, then what exactly does he believe we should be spending our time in math class teaching? This inquiry led me to his blog, where I found a list of 5 major areas he believes we should be focusing on (along with his own reasons for each):

- Data Science (everything data, incorporating but expanding statistics and probability).

- Geometry (an ancient subject, but highly relevant today)

- Information Theory (everything signals–whether images or sound. Right name for area?).

- Modeling (techniques for good application of maths for real world problems)

- Architecture of Maths (understanding the coherence of maths that builds its power, closely related to coding).

Now what?

Looking at the list above, I know that some of these can be found in Willows classrooms. Ultimately, the true purpose of the Symposium was to give vital food for thought to our school community and beyond about what could be possible in today’s math classroom. Since the Symposium, we’ve had Learning Lunches for grades DK-5 plus middle school math and science teachers to give everyone a time and place to properly reflect on everything. Further, just this week we invited parents to attend a Learning Breakfast led by Gary Stager, where we discussed the key ideas from the Symposium with parents.

And the conversation continues…

and I were aligned philosophically on the need for learning commons for elementary, middle, and college students with comfortable, flexible spaces to learn and collaborate as a group and study individually. Like Berkeley, our own Director of Library Services, Cathy Leverkus, has been very forward thinking, envisioning our library as a communal space, adaptable and ready to offer differentiated learning and new configurations that best meet our students’ needs in our constantly changing world.

and I were aligned philosophically on the need for learning commons for elementary, middle, and college students with comfortable, flexible spaces to learn and collaborate as a group and study individually. Like Berkeley, our own Director of Library Services, Cathy Leverkus, has been very forward thinking, envisioning our library as a communal space, adaptable and ready to offer differentiated learning and new configurations that best meet our students’ needs in our constantly changing world.

We share, question, and grow together. Our learning commons enhances this collaboration, which is a hallmark of The Willows educational approach, and is instrumental in shaping the soul and culture of our school.

We share, question, and grow together. Our learning commons enhances this collaboration, which is a hallmark of The Willows educational approach, and is instrumental in shaping the soul and culture of our school. The space is almost museum-like with high walls and skylights. The light and air are conducive to learning.

The space is almost museum-like with high walls and skylights. The light and air are conducive to learning. An example is the Kindergarten Maker replica of the Mayflower complete with wind machine, which would be impossible in a classroom, but is an exciting learning experience in the Willows 1 common space. All our spaces are intentionally flexible offering a myriad of learning experiences and cross-disciplinary and multi-age opportunities. In our learning commons, our middle school students often buddy with our youngest students assisting in hands-on projects that are the very heart of our DK-8 model, building empathy and offering leadership opportunities.

An example is the Kindergarten Maker replica of the Mayflower complete with wind machine, which would be impossible in a classroom, but is an exciting learning experience in the Willows 1 common space. All our spaces are intentionally flexible offering a myriad of learning experiences and cross-disciplinary and multi-age opportunities. In our learning commons, our middle school students often buddy with our youngest students assisting in hands-on projects that are the very heart of our DK-8 model, building empathy and offering leadership opportunities.

With unprecedented amounts of time, our students were able to build real expertise, often with new skills or concepts. Immersed in their projects, they were more willing to take risks, to persevere through difficulties, to collaborate and problem-solve with peers, and to see the true value in what we call “hard fun.”

With unprecedented amounts of time, our students were able to build real expertise, often with new skills or concepts. Immersed in their projects, they were more willing to take risks, to persevere through difficulties, to collaborate and problem-solve with peers, and to see the true value in what we call “hard fun.”

Ultimately, in my mind, time and engagement go hand in hand. Without the time to really dive deeply into something, engagement will always remain superficial while everyone moves on to the next regularly scheduled block of learning. When children are shown that educators truly value their strengths and interests and are willing to give them time to immerse themselves in meaningful projects, they really rise to the occasion.

Ultimately, in my mind, time and engagement go hand in hand. Without the time to really dive deeply into something, engagement will always remain superficial while everyone moves on to the next regularly scheduled block of learning. When children are shown that educators truly value their strengths and interests and are willing to give them time to immerse themselves in meaningful projects, they really rise to the occasion.

Regarding smartness, she asked us to consider who students usually consider to be smart in math: those students who are the fastest and most efficient with calculating. Much like Conrad Wolfram, Horn insisted this is much too narrow a view of what constitutes smartness in math. To illustrate her point, we watched part of a

Regarding smartness, she asked us to consider who students usually consider to be smart in math: those students who are the fastest and most efficient with calculating. Much like Conrad Wolfram, Horn insisted this is much too narrow a view of what constitutes smartness in math. To illustrate her point, we watched part of a  True to her constructivist perspective, she was emphatic that these games be played independently of any formal math instruction – that is, teachers should not be pointing out to students that they are adding or subtracting before, during, or after playing the games. Students must construct their own meaning, and this is achieved only through repeatedly playing the games, revisiting the concepts over and over again.

True to her constructivist perspective, she was emphatic that these games be played independently of any formal math instruction – that is, teachers should not be pointing out to students that they are adding or subtracting before, during, or after playing the games. Students must construct their own meaning, and this is achieved only through repeatedly playing the games, revisiting the concepts over and over again.